monoculture

by

Lana Nguyen

︎︎︎

(Writing)

![]()

In April, while everyone was distracted under the cloak of the evolving pandemic, Footscray Primary School cut the last Vietnamese bilingual education program in this country.

With it left the strongest standing structure for Vietnamese language learning. This program was the legacy of the large Vietnamese refugee population in Melbourne’s western suburbs coupled with the radical language policy that migrants from different backgrounds had built from the ground up in the 1980s. Starting off as a mother-tongue maintenance program, the Vietnamese bilingual program grew from the belief that cultural ties were pivotal to personhood.

However, in a colonial country where language erasure has often been used as a weapon to shield and empower White Australia, it shouldn’t have been surprising that over time programs like this one were being under-supported and dismantled. But it was still a shock to many people with links to Melbourne’s west and the Vietnamese community there.

We thought at least that in Footscray – the suburb where the Vietnamese Museum is set to be built; the suburb that everyone knows for its Vietnamese restaurants, businesses and markets; the suburb where Vietnamese is the second most spoken language – everyone would find it absurd to replace a Vietnamese bilingual language program with an Italian one.

According to the decision makers at Footscray Primary School, the logic behind the change was that Italian was more widely taught and therefore easier to learn. It was Latin-based and closer to English. It was better established in the education system, with a larger pool of teachers, resources and expertise.

Italian had stronger roots and relationships to the language that most people already use across the country, and it had a stronger connection to what people in power knew. Fluency in English was what allowed them to rise up the ranks, be vocal on boards, and be in a position where they had the power to change the next generation. Italian is closer to their version of success.

A majority-white school and departmental leadership dismissed and ignored the concerns of the Vietnamese community, who knew that without this program, they would lose what was already becoming worn through time and distance. The school was unwilling to understand our intricate ways of knowing language and history – our ways of speaking, knowing, listening and seeing, our lineages that hold land, war and love.

The decision to axe the last bilingual program accelerated the cumulative cycle of cultural decay: Vietnamese would now be taught less at primary school, even fewer students would pursue it in high school, and only a handful would carry it through into university and become Vietnamese teachers. As a result, schools would not offer the language, because there aren’t enough teachers. They’d choose a language that does have that support – maybe something Latin-based, something easier to succeed in, something that is used more widely, something familiar and adjacent to a prestigious and powerful language.

***

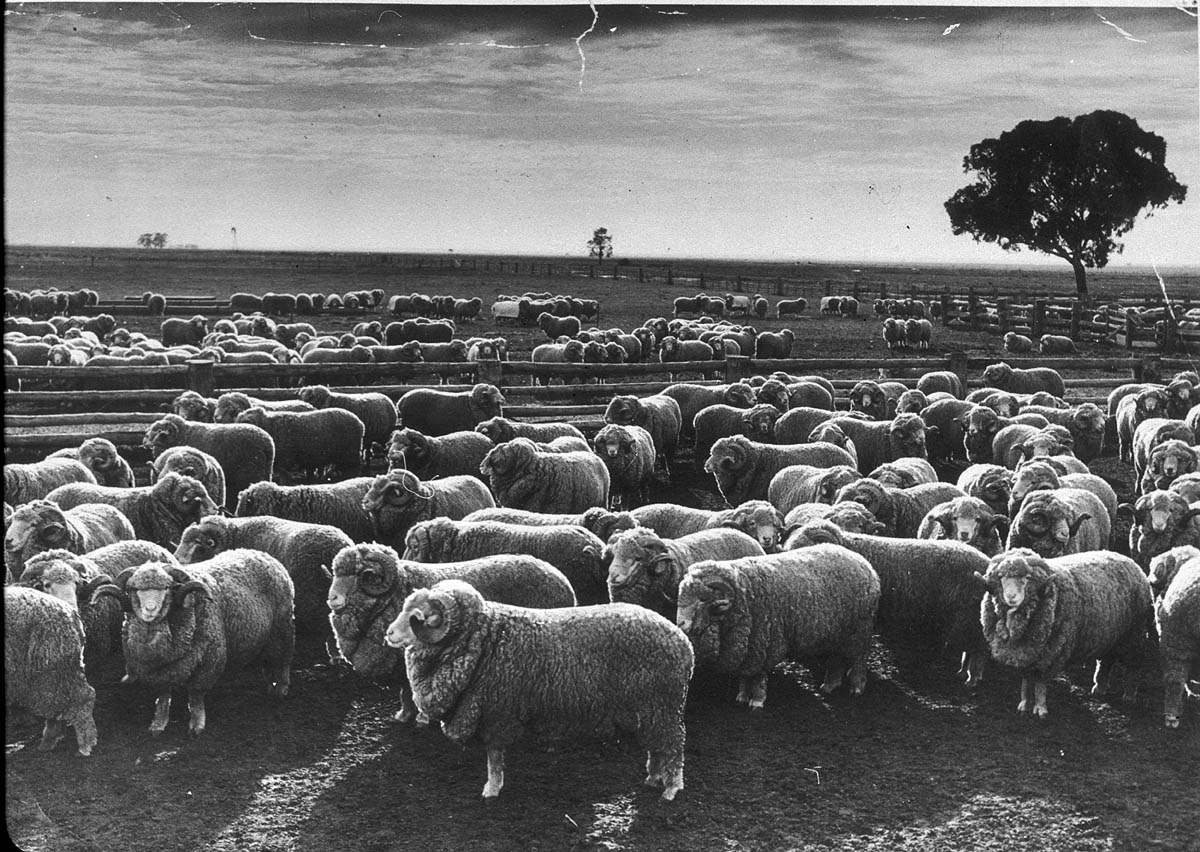

When the same crop is grown on the same land year after year, the nutrients in the soil are depleted. Repeating demands by the same plants make the soil brittle, losing its structure, eventually creating an arid, infertile expanse where seeds no longer can take root.

Over time, farmers who practise monoculture often have to buy chemical fertilisers to grow their crops on damaged earth. When they do manage to get something to grow, due to lack of biodiversity, the crop is more susceptible to pests, storms and disease with no other plants to bring beneficial bugs and nutrients to the soil.

The run-off from chemical fertilisers often creates algal blooms in rivers, tipping the balance of their ecosystems. Fish die, often due to a lack of oxygen from the competition in the waters, and down the track the creatures that eat the fish do too. The situation snowballs, toppling everything in its path.

Language as a monoculture does the same. Many monocultures have the same trajectory, depleting and poisoning the world around them.

The echo chamber of language, the echo chamber of art, the echo chamber of power is a destructive force – life can’t thrive in a monopoly.

The same thing over and over again, a continuous conveyor belt, needs a continuous amount of energy. Eating everything around it, until it begins to eat itself. A black hole. A white hole. A white cube.

When culture gets siloed as an industry, a profession, different from our day-to-day lives, an other, it becomes vulnerable to attack. It’s no longer integrated in the ecosystem of our lives. It easily becomes the first thing off the chopping block when push comes to shove.

Art sitting with activism, art sitting outside the establishment, art moving beyond monocultural leadership: this is necessary to stop a sure-fire decay. At the precipice of irrelevance, organisations and industries can move to reflect on and nurture the complexity of the worlds they work in. The capillaries between differences – between industries, between languages – are integral for creating a healthy ecosystem, an ecosystem that is resilient to change through a synergy of support.

Robin Wall Kimmerer, in her book Braiding Sweetgrass, writes about the beautiful reciprocity between asters and goldenrod as the placement of these purple and yellow plants side by side attracts bees with their contrast. The bees come to this colour feast and pollinate the flowers. They create seed, and more life begins.

Having multiple ways of being, speaking, knowing and doing make for an abundant world. A soup of possibility to share. A network that is stronger because of its multiple parts.

So what do we do when the world is separated into individual pieces and put into a hierarchy? What do we do when one familiar way of being and knowing is prioritised at the expense of the others?

***

The campaign to Save the Vietnamese Bilingual Program at Footscray Primary School has not reached its goal of having the program reinstated.

Despite over 17,000 petition signatures, multiple radio interviews, coverage in mainstream media, and many letters to local MPs, school leadership and the Department of Education, nothing has changed. The likelihood is that it won’t.

It’s disheartening to know that despite all the dedicated effort and care put in to try to save the program, an unrepresentative leadership has ruled against even a conversation with Vietnamese community organisations, the upset parents and the wider community who see Vietnamese culture and language as a significant part of the neighbourhood – something to be protected and nurtured. This is what happens when power is structured as a monoculture: it fails in its responsibility to adequately understand and govern in service to the many. It models success as a version of itself.

The soil is too degraded.

Instead, the campaign now is looking to install a Vietnamese bilingual program somewhere there is enough supportive leadership to make it work – a good expanse of healthy soil. Somewhere it is valued as part of the ecosystem, so it can uniquely give back in return.

I got involved with the campaign to save the program primarily because I am part of the Vietnamese community and I know personally that our language is already facing immense loss. However, the fight goes beyond keeping this particular language in this particular school.

It’s not just about Vietnamese: it’s about all immigrant languages, Indigenous languages, languages that are farther from English in their structure, their distance, and their knowledge.

It’s a fight against the colonial mentality in this country that attributes value only to a certain subsection of people, prioritising the familiar. A streamline, a narrowing, a monoculture.

***

I’ve been learning Vietnamese every Sunday over Zoom. It’s excruciatingly hard. I learnt French in high school and university and neither French nor English is tonal. Vietnamese is far from what my tongue is used to – the difference between a rice seedling, mạ, and ghost, ma, is just a small inflection.

My Vietnamese isn’t fluent, and it’s unlikely that it will ever be, but that’s where I stand as someone of the second generation, and it’s from here I’ll attempt to weave the path in between – using my fluency in English as a bridge to carry the ideas from my Vietnamese lineage to those in power, using my growing knowledge of Vietnamese to change the way I use English. Like asters and goldenrod, the contrast will create the opportunity.

In cases like this campaign at Footscray Primary, a fight for co-existence won’t be enough. The momentum of the colonial project has already taken hold. There isn’t enough of an opening for change, or room to flourish. The air is stale and the walls are rigid.

But where there is a slight crack, movement enough to change the shape of the structure, to bring in multiple knowledges, to widen the frame, there is the possibility of life.

In my life and work, I want to look at tangible power and how we shift into spaces of cooperation, interdependence and collaboration – how we work gently and how we work together. Working towards thickening the lines between the diaspora and its history, the first and second generation of Vietnamese refugees, solidarity between communities and between ways of working, deepening the connections between art and activism.

I will also be making sure to direct any artistic collaborations to schools that do support a more expansive and interesting world, moving my soft power to try to wedge a cow and a dog in the closing gates of assimilation and gentrification – like James Nguyen, making chó bò.

This article was written on Wurundjeri land, a land that has also been rapidly changed by a violent hierarchy of value. I pay my respect to Wurundjeri elders past, present and emerging who have and continue to feed this land with care and coexistence.

For more information on the campaign to Save the Vietnamese Bilingual Program at Footscray Primary School, you can go to the petition and website.

To support Vietnamese bilingual advocacy more broadly, you can visit here.

About the writer:

LANA NGUYEN is an independent creative producer and arts worker interested in experimental, site-specific and context-driven work. Interested in the space where community and contemporary practice align, she looks to create work that drives conversation and connection. She works by listening, asking questions and through collaboration with others.